Min morfar

Klas and Sigrid had a sole child, rather late in life*: my mother Eva. When she married an Englishman it must have distressed them to think of her making her home so far away from Sundsvall. But when I was born and we returned for a long visit, their delight in their grandson is easy to imagine. There are many photos of a proud Morfar with me when I was a baby boy who had inherited his blue eyes. For a man who never had a son, to have a grandson would have meant a lot.

But as it turned out grandfathers would never play a large part in my life. I barely knew my English grandfather, meeting him only twice so far as I recall. And Morfar+ (Klas) died on the morning of Christmas Eve when I was about ten. I remember my mum's anguish when she answered the telephone. So far away! Later that day, I thought how strange it was to be unwrapping a Christmas present from someone who had already died. (It was a reclining dog, with a nodding head.)

Morfar had had a bad stroke around five years before, affecting both his speech and his mobility. In England my early bilingualism had foundered. We could only afford to visit Sweden every other year, so Morfar and I never had much chance to overcome the language barrier. After the stroke I became rather afraid of him; I was always a shy child.

Once we were alone together in the living room of the flat. I was playing by myself. Morfar was sitting in his invariable armchair, well dressed as ever (Morfar always wore a tie). Suddenly he rose: he wanted, I thought, to show me a kindness and to bring us closer together. He managed a step or two, and then he collapsed to the floor. "Morfar's fallen over!" I shouted, very alarmed. Mormor and my mother came running from the kitchen. They settled him down, but the emotional barrier between us, as much as the language barrier, never thawed any further. I loved him because he was my Morfar but I never knew him as a real person.

Morfar had had a bad stroke around five years before, affecting both his speech and his mobility. In England my early bilingualism had foundered. We could only afford to visit Sweden every other year, so Morfar and I never had much chance to overcome the language barrier. After the stroke I became rather afraid of him; I was always a shy child.

Once we were alone together in the living room of the flat. I was playing by myself. Morfar was sitting in his invariable armchair, well dressed as ever (Morfar always wore a tie). Suddenly he rose: he wanted, I thought, to show me a kindness and to bring us closer together. He managed a step or two, and then he collapsed to the floor. "Morfar's fallen over!" I shouted, very alarmed. Mormor and my mother came running from the kitchen. They settled him down, but the emotional barrier between us, as much as the language barrier, never thawed any further. I loved him because he was my Morfar but I never knew him as a real person.

* Not late in life by today's standards. Klas was 44 and Sigrid just 30.

+ Swedish has two words for grandfather:

morfar: mother's father

farfar: father's father

Likewise mormor (mother's mother) farmor (father's mother), moster (mother's sister), faster (father's sister), morbror (mother's brother), farbror (father's brother)

morfar: mother's father

farfar: father's father

Likewise mormor (mother's mother) farmor (father's mother), moster (mother's sister), faster (father's sister), morbror (mother's brother), farbror (father's brother)

*

|

| Henrik, my great-grandfather |

|

| Karolina, my great-grandmother |

Klas Henrik Gulliksson was born on 7 July 1892. Three months before he was born, his father Henrik had died of pneumonia. His mother Karolina lived on for many years after her husband's death; my mother knew her.

Henrik was a good "snickare" (carpenter). He made the large rocking-chair that still gets passed around the family and is currently at my sister Annika's house. He also made the blue cabinet at Battle which is a "sockerskrin". It was designed to hold loaf sugar. The sugarloaf went into the upper drawer and was banged with a hammer to break it up. This drawer was kept locked, but small fragments would fall down into the narrow middle drawer, which the children could access. There was also a lower drawer with a lock (perhaps for the next loaf?)

Klas had four elder siblings. Henning, Hildur, Lydia and Karl, who was just two years older than Klas.

Three days after Henrik's sudden death, a lady visited and offered to adopt little Lydia, then about four; it wasn't unusual in those days. But Karolina would rather have starved than lose pretty Lydia.

Henrik's death certainly put the family in difficult circumstances. Karolina had been a teacher at Borgsjö before her marriage, but now when she re-applied she was refused. She had become a Baptist, and could not teach in schools linked to the Church of Sweden.

So, instead, she resorted to sewing waistcoats. Hildur, then about nine years old, was often left in sole charge of the other children: Lydia and the two baby boys. Henning, the eldest son, was the only child to receive a full education.

Karl and Klas, those two young boys, tumbled up together. They were a naughty pair. When Karl was only four he threw a fork at two-year-old Klas. Karolina found it sticking out of Klas' pate; apparently no serious damage was done. When they were a bit older they sneaked off to swim in Selångersån (Sundsvall's river) or to creep under the chain and ski down the out-of-bounds slope beneath the ski-jump on Södraberget. They became excellent at swimming and skiing.

|

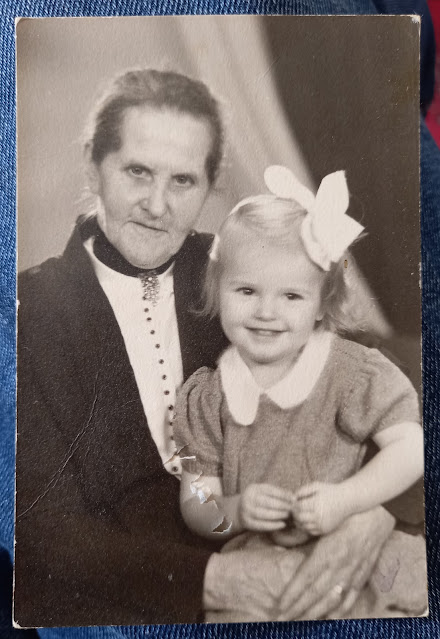

| Karolina with her grand-daughter Eva (my mum) |

|

| Klas, Lydia, their mother Karolina, and Karl |

Henning Gulliksson

The family could only afford to educate one of the children. That was Henning. When he was at home, he passed on his knowledge to his brothers and sisters. Henning became relatively well off.

When my mother was two, the house Klas and Sigrid moved into (Fridhemsgatan 11 in Sundsvall) was Henning's: Klas couldn't afford to buy his own. Henning built the house with a man called Fritiof Lindgren. Henning had one half of the house and Lindgren had the other. Henning lived there with his first wife Svea until her death.

Henning and Svea had one child, a little girl who died after just three days.

(My mum was born to Klas and Sigrid three years later, and she was treated with perhaps painful protectiveness, because she was in effect the only child on either side of her family; Klas and Sigrid were not young parents, and all Klas' and Sigrid's siblings were either single or childless or had emigrated to America, never to be seen again.)

For Svea the whole thing was so traumatic that she swore never to go into hospital again. She died, a few years later, of a burst appendix.

It was after Svea's death that Henning moved to Stockholm in connection with a job in publishing. Thus Fridhemsgatan 11 became available for Klas and Sigrid to rent.

Both Albäcksgatan and Fridhemsgatan are in the suburb Södermalm (though the Fridhemsgatan house is very close to Östermalm). Södermalm was a residential expansion of Sundsvall, south of the railway. The name was changed in about 1900; it was formerly Stenhammaren, which had acquired something of a reputation as a red light district. (The novelist Lars Ahlin was born in Södermalm in 1915.)

|

| Fridhemsgatan 11 |

Eva, my future mum, stood in the street and told the passers-by: "I used to live at Albäcksgatan 4 and now I live at Fridhemsgatan 11."

Klas and his family had only moved a few hundred meters. Albäcksgatan 4 had belonged to Sigrid's invalid father Karl. They moved in so they could take care of him. He died when Eva was only one year old.

At Fridhemsgatan Fru Wahlström, Svea's mother, still lived upstairs. Klas and Sigrid shared the house with her when they moved in.

Tant Lindgren lived next door, with her daughter Babbo. Babbo was a a bit older than Eva. Eva was struck by Babbo possessing a record-player, a rare thing at the time. (This was the Babbo who married Ingvar. In my youth we used to visit Babbo and Ingvar on our way north; they had an apartment in Nyköping.)

My earliest datable memory is from that house: a Christmas when I was three. Jultomten (Santa Claus) visited the house that day. He scraped the snow off his boots and announced: "Here is a present for a little boy who is three." I hesitated, being a stickler for accuracy, and said "Well, I'm three and a half!" The present was a metal pick-up truck, coloured orange and white, with a crane and a hook you could wind up and down.

Fridhemsgatan 11 was a lovely wooden house, with Falu Röd Färg (dark red) walls and white-painted window and door frames: the traditional colours of such houses. They only occupied the downstairs: there was another tenant above them. This was where my mother grew up; it was where she had to be detached after licking the metal doorknob when it was 20 below, and where she had a miniature pipe-organ, which was supposed to help her learn the piano.

The house had a fine cellar and a big garden containing currant and gooseberry bushes as well as raspberries along the back fence. In my summer memories the garden is always sunny, but in winter it got no sun at all for six months, because of the rising slope of the South Mountain just behind. Around the time of Morfar's stroke they moved to a third-floor apartment on the north side of town: Elevgränd 4B. Of course I remember this flat much more clearly than Fridhemsgatan, but that's for another post.

Lydia

I and Annika remember Lydia very well, though not, I am sure, the way she should best be remembered. When we were very young Lydia, who never married, had her own flat in Sundsvall. I remember her as an elderly woman with short black hair, a strict Baptist, teetotal and a bit austere (but she's laughing heartily in the photos where she's giving me a carry). Around the same time as her younger brother Klas, she suffered a catastrophic stroke. After that she lived a lingering half-life in care homes for another decade or more. Visiting Faster Lydia was a regular and dreaded part of our annual holiday in the north. She lay there like a frail bundle of bones, scarcely a hump beneath the bedclothes: the bed was a narrow single bed but she made it look big. Mum and Dad spoke to her and went through rituals of greeting, talking about the holidays, pointing out us children (who added our weak smiles), or a new bunch of flowers beside the bed, and so contriving to eke out a near-monologue. The ghastly Lydia, with well-combed thin white hair, was unfathomable, barely capable of a syllable or flicker of feeling. I don't know if Lydia had Alzheimer's or was simply too weak to say or feel anything. Mum would stay a bit longer while we and Dad went off to the beach at Björkön. When the visit was over we cried, but not much: we'd cried before, but nothing would or could ever change, so what was the point.

It was only many years later that I began to be interested in my family past and to learn what a dynamic and active woman Lydia had been. She decided never to marry while her mother was still alive, in order to look after her. She must have been about fifty by the time Karolina died, and she never did marry.

Klas

So, my grandfather. Most of what I know about Klas's younger life is encapsulated in the page of the family album shown at the head of this post.

He's standing in the middle of the group of five revellers. They could be anywhere in northern Sweden, but I've always imagined this photo shows either the North or South mountain in Sundsvall: both popular locations for a day out. The girl beside him isn't Sigrid, so perhaps she was an early flame; or it could be his sister Lydia. (An old photo of Sigrid appears at the bottom right.)

In 1924 Klas became a cargo inspector at the docks in Sundsvall. (Coincidentally, the same job my great-uncle John did at Southampton.) At the docks he was known as "Gullik". In Swedish, his job was "kajbokhållare": that is, dock book-keeper.

By the time they moved to Fridhemsgatan Henning had a good job in Stockholm. He was an editor for a major publisher, perhaps Bonniers but no-one is sure. Like many Swedish dignitaries he was a Good Templar, that is, a strict teetotaller. It was important for his reputation that he never even attended a gathering where alcohol was served. When my mother and father got married in 1957, the toasts were in sparkling pear juice!

Despite or perhaps because of being a Good Templar, Henning was an affable presence at parties and led the wedding guests in the singing of traditional Swedish drinking songs (snapsvisor) such as the evergreen "Helan går", which you might paraphrase as "Down the hatch". He appreciated everything about drinking culture except the alcohol itself. My father remembers that when they visited his flat in Stockholm Henning proudly showed off his collection of small bottles of various choice tipples -- all non-alcoholic, naturally.

I don't remember Farbror Henning but we must have met each other once or twice when I was still a baby. His death was a sad accident. He slipped on an icy street and slid under a moving bus. He was run over by the rear wheels.

I don't remember Farbror Henning but we must have met each other once or twice when I was still a baby. His death was a sad accident. He slipped on an icy street and slid under a moving bus. He was run over by the rear wheels.

When I was a little older we used to stay at Faster Selma's apartment in Stockholm: one of several stopovers on our long journey north. Selma had been Henning's second wife and was now his widow. I remember her cloudily: a tea-party, and some forgotten joke about jam. Usually we stayed at the apartment when Selma wasn't there. Probably she was away at a summer cottage, like most Stockholm residents at that time of year.

As it happened it was through Selma that we acquired our own summer cottage. She put us in touch with her sister Esther, who lived in Sollefteå with her husband Helge. They had a summer cottage in the Indal valley, but family troubles meant they hadn't gone there for eight years. It had no electricity or water. When we went over to look at it we had to battle through the young forest that had already grown up. For forty years it became our heaven on earth.

Hildur emigrated to the USA. She got married there and became Hildur Nordine.

I've managed to find a little more genealogy related to her husband Carl . Carl Axel Nordine (1889 - 1943) was six years her junior.

She had four children. Her son Ivan died in the Vietnam war. One of the daughters was Alice Linnea ("Lin"). My mother was in touch with her and met her once in the 1980s -- she was Lin Roy then --at her home in Exeter, New Hampshire.

|

| Hildur Gulliksson |

|

| Lydia Gulliksson |

|

| Lydia Gulliksson |

Lydia

I and Annika remember Lydia very well, though not, I am sure, the way she should best be remembered. When we were very young Lydia, who never married, had her own flat in Sundsvall. I remember her as an elderly woman with short black hair, a strict Baptist, teetotal and a bit austere (but she's laughing heartily in the photos where she's giving me a carry). Around the same time as her younger brother Klas, she suffered a catastrophic stroke. After that she lived a lingering half-life in care homes for another decade or more. Visiting Faster Lydia was a regular and dreaded part of our annual holiday in the north. She lay there like a frail bundle of bones, scarcely a hump beneath the bedclothes: the bed was a narrow single bed but she made it look big. Mum and Dad spoke to her and went through rituals of greeting, talking about the holidays, pointing out us children (who added our weak smiles), or a new bunch of flowers beside the bed, and so contriving to eke out a near-monologue. The ghastly Lydia, with well-combed thin white hair, was unfathomable, barely capable of a syllable or flicker of feeling. I don't know if Lydia had Alzheimer's or was simply too weak to say or feel anything. Mum would stay a bit longer while we and Dad went off to the beach at Björkön. When the visit was over we cried, but not much: we'd cried before, but nothing would or could ever change, so what was the point.

It was only many years later that I began to be interested in my family past and to learn what a dynamic and active woman Lydia had been. She decided never to marry while her mother was still alive, in order to look after her. She must have been about fifty by the time Karolina died, and she never did marry.

I'll find out properly one day, but I know she was heavily involved, I think as a teacher, in church charitable work. She worked as caterer at the Baptist retreat at Mjösjö, a remote but pretty spot in the hinterlands (Bräcke kommun, Jämtland), about 100km from Sundsvall. Originally it was a place where Baptist pastors could take a summer holiday with their families. But during WW2 it became an orphanage, taking children from both Finland and Norway. (Lydia got medals from the Finnish refugee organisation. ) Later it was involved with the "kolonibarn" charity, providing summer holidays for the children of the urban poor.

My mum went there in her tenth summer, making friends with Anita Björnsson, a girl of the same age who lived in the farmstead next door (there were only about three houses in Mjösjö).

My mum remembers an occasion when they walked two spaniels together, and made the mistake of letting the dogs off the lead. The dogs promptly went off gallivanting in the forest and didn't respond to the girls' calls. It didn't go down very well at home, though the dogs did drift back eventually.

Anita's home struck Eva as quite strange. There were so many flies in the kitchen that you could hardly raise the juice to your lips, but no-one seemed to notice. Anita lived there with her mum, but Eva never met her dad, who seemed to be always away. They were allowed to play in "his" house (a separate building). Here they found lots of empty bottles, which (coming from the Baptist establishment) made a very grave impression on little Eva.

When she was a little older Eva went back to Mjösjö, this time as a volunteer helping with the kolonibarn.

Many years after that, Mum and Dad went back and they found Anita still living at Mjösjö. She loved the horses and had taken on the farmstead. Her life was a strange contrast with her rather glamorous sister Monica, who had gone off to Italy at the earliest opportunity.

Karl

Like Hildur, he emigrated to the USA. He went there at a young age, perhaps 20 or even younger. He was unsettled in northern Sweden. In his early years the other children used to call him "Nigger", in reference to his dark complexion and prominent lips.

Karl

Like Hildur, he emigrated to the USA. He went there at a young age, perhaps 20 or even younger. He was unsettled in northern Sweden. In his early years the other children used to call him "Nigger", in reference to his dark complexion and prominent lips.

He was a house painter by trade. When he got to America the family lost touch with him for many years. We can only guess why. Perhaps one issue was the family's strict religiosity. In America, Karl married a Swedish woman who had been married before. That might have been unacceptable to Karolina. Karl and his wife had one child, a boy.

All this was only discovered when, years later, Karl unexpectedly showed up at his sister Hildur's place (in New Hampshire?). Only then did he learn of his mother's death, years before; there had been no means of telling him.

Whatever the reasons for this isolation, Karl made a new life for himself in America. I'm not sure whereabouts he lived, but when he died the local newspapers praised his energetic contribution to the life of the community.

|

| Klas Gulliksson |

Klas

So, my grandfather. Most of what I know about Klas's younger life is encapsulated in the page of the family album shown at the head of this post.

By the age of thirteen he was working. His first job was as a beater in a fur factory. Something made his lungs bleed: fluff or leather fibres or dust, I'm not sure which.

He was "in the cavalry" as a young man, but what cavalry, and for how long, I don't know. Then he was a wage clerk for the railway during the building of "Östkustbanan": the new coastal route from Gävle - Sundsvall - Härnösand, now the principal rail route to the north, opened in 1927. The photo of the logging camp may come from this period. Taking the week's wages to the camps and distributing them to the workers was a responsible job, though not a well-paid one.

He was "in the cavalry" as a young man, but what cavalry, and for how long, I don't know. Then he was a wage clerk for the railway during the building of "Östkustbanan": the new coastal route from Gävle - Sundsvall - Härnösand, now the principal rail route to the north, opened in 1927. The photo of the logging camp may come from this period. Taking the week's wages to the camps and distributing them to the workers was a responsible job, though not a well-paid one.

|

| Klas on a converted motorbike |

He's standing in the middle of the group of five revellers. They could be anywhere in northern Sweden, but I've always imagined this photo shows either the North or South mountain in Sundsvall: both popular locations for a day out. The girl beside him isn't Sigrid, so perhaps she was an early flame; or it could be his sister Lydia. (An old photo of Sigrid appears at the bottom right.)

|

| Klas and Sigrid (a wedding photo?) |

|

| Klas and Sigrid a few years later |

|

| Klas' signature, on Eva's high school report for Spring term 1952. ("målsman" means "guardian") |

In 1924 Klas became a cargo inspector at the docks in Sundsvall. (Coincidentally, the same job my great-uncle John did at Southampton.) At the docks he was known as "Gullik". In Swedish, his job was "kajbokhållare": that is, dock book-keeper.

My mum regrets not knowing her dad better. She never had the time with him that she had with her mum. She left Sweden when barely 18, and it wasn't long after his retirement that Morfar had a bad stroke which impacted his communications with everyone, not just me.

She remembers him as a quiet and good man, proud of being able to earn enough money to keep his small family. He was usually at work. He often had to go down to the harbour in the middle of the night, if there was a boat coming in and goods to be checked. His holidays were in January, when the harbour was icebound.

He retired on the 12 March 1963, when he was seventy. I know this because I'm looking at the Seamaster watch he was presented with. The watch is engraved "Långvarig trogen tjänst" : the standard phrase for these occasions, meaning "long faithful service". The watch is one of those self-winding ones: I've given it a good shake and it's working, after at least ten years of lying in a drawer.

*

Karolina (Klas' mother)

Karolina had travelled from Värmland with her father when he came to Sundsvall looking for work. She was 9 years old at the time. They travelled by horse and cart. I suppose this was around 1870. Karolina's mother and siblings remained in Värmland until the father was properly settled in Sundsvall.

Karolina baked and sold food at the factory gates on payday (Friday afternoon).

Later, she was an itinerant teacher at Borgsjö, 80km west of Sundsvall in the Ljungan valley. (Sundsvall, on the east coast of Sweden, lies between the mouths of two major rivers, the Indal just to the north and the Ljungan just to the south.)

I'm not sure how many siblings Karolina had, but she was the eldest.

Klas's cousins

Karolina had a younger sister (moster Marie), who married a Herr Floberg and had two sons, Johan and Albert.

Johan Floberg had a farm at Johannisberg, a little downriver from Borgsjö. His wife's name was Hilda.

*

Karolina (Klas' mother)

Karolina had travelled from Värmland with her father when he came to Sundsvall looking for work. She was 9 years old at the time. They travelled by horse and cart. I suppose this was around 1870. Karolina's mother and siblings remained in Värmland until the father was properly settled in Sundsvall.

Karolina baked and sold food at the factory gates on payday (Friday afternoon).

Later, she was an itinerant teacher at Borgsjö, 80km west of Sundsvall in the Ljungan valley. (Sundsvall, on the east coast of Sweden, lies between the mouths of two major rivers, the Indal just to the north and the Ljungan just to the south.)

I'm not sure how many siblings Karolina had, but she was the eldest.

"Farmor" was the only grandparent Eva knew. She was a good singer and used to sing Eva old Swedish songs like "Klang min vackra bjällra". She sang in the choir at Elim Kyrka (the Baptist church), as did her daughter Lydia.

"Farmor" lived in Långgatan (sometimes Lydia lived there too). She had a milk shop there. (The premises were later a "Tinghuset". During summer visits to Sundsvall we often went there and, of course, every time we retold the story that it had once belonged to Mum's gran.)

Milk was delivered to the shop in large churns, and Karolina used a liter-scoop to fill the containers brought by the general public. Sigrid often helped out at the shop, and Eva was a regular visitor.

One summer day, when Eva was five or six, she went with the neighbour sisters Ing-Britt and Astrid Hallberg to the Sundsvall park called Vängåvan where there was a "plaskdammen" (splash pool). Ing-Britt was a few years older than Eva. Astrid was her own age, but a bit backward due to illness in infancy. Eva wore only her bathing costume, but just as in later years she was always a bit hesitant about getting in the water and when they arrived at the park she refused to get in. Ing-Britt had the bright idea of getting her to take off her bathing costume and then immersing it, thinking that when Eva put the wet costume back on she would then have the courage to get in the pool. But it didn't turn out that way. Instead, Eva refused to put on the damp costume, and instead carried it all the way to Långgatan. Karolina answered the knock and was surprised to find her naked grand-daughter standing outside. Hence the longstanding family joke that my mum once walked naked through the streets of Sundsvall!

(Fru Hallberg was a neighbour. She had a fabric shop -- tygaffär -- in Sundsvall.)

|

| Johan and Hilda Floberg |

Klas's cousins

Karolina had a younger sister (moster Marie), who married a Herr Floberg and had two sons, Johan and Albert.

Johan Floberg had a farm at Johannisberg, a little downriver from Borgsjö. His wife's name was Hilda.

At the farm they needed help at hay-making time, and my mother went there with Klas at least once (she speculates that Klas couldn't get away very easily at that time of year, a busy time in the harbour). My mother remembers pitching hay up on to the rick and sitting on the top of it. The Johannisberg farm, like many others, contained two homes: a cosy winter one and a more open summer one. Another memory: Hilda setting out food for the workers in the veranda (farstubron) outside the summer home.

The Flobergs had two daughters, Elsie and Jonny, and a son Pelle.

Elsie and Jonny both married. Jonny's husband was a musician who played in a dance band. They had two children, Benny and Ingerla.

Pelle was the youngest. He was a few years older than my mother; he was good-looking and bright and he received more education than most. At one time he got a job in a chemical factory outside Sundsvall, making plastics, and then he stayed for several months with the family at Fridhemsgatan.

A little further up the Ljungan valley from Borgsjö and Johannisberg is Ånge, and here my mum had another distant relative.

Tant Judith Siljeström, who had a daughter called Lillemor, was related in some way to Johan Floberg (presumably on his father's side). The Siljeströms had a big house and were well off, they owned a shop and were considered more genteel than mere farmers. Tant Judith was very fond of Klas's sister Lydia, who had rather genteel manners herself.

Photo taken outside Lidens Gamla Kyrka. Michael in the arms of Moster Anna, Mum, Mormor, Morfar and a pal whose name I don't know.

*

*

Zone S, number 116 in the cemetery at Sundsvall. It says:

KARL GUSTAFSSON

*1868 +1937

HUSTRUN AMANDA

*1872 +1927

DÖTTRARNA

ANNA *1898 +1976 (moster Anna)

GRETA *1901 +1988 (moster Greta)

KLAS GULLIKSSON. (morfar)

*1892 +1968

HUSTRUN SIGRID (mormor)

*1906 +1997

Hustrun = wife

Döttrarna = daughters

The Flobergs had two daughters, Elsie and Jonny, and a son Pelle.

Elsie and Jonny both married. Jonny's husband was a musician who played in a dance band. They had two children, Benny and Ingerla.

Pelle was the youngest. He was a few years older than my mother; he was good-looking and bright and he received more education than most. At one time he got a job in a chemical factory outside Sundsvall, making plastics, and then he stayed for several months with the family at Fridhemsgatan.

A little further up the Ljungan valley from Borgsjö and Johannisberg is Ånge, and here my mum had another distant relative.

Tant Judith Siljeström, who had a daughter called Lillemor, was related in some way to Johan Floberg (presumably on his father's side). The Siljeströms had a big house and were well off, they owned a shop and were considered more genteel than mere farmers. Tant Judith was very fond of Klas's sister Lydia, who had rather genteel manners herself.

Photo taken outside Lidens Gamla Kyrka. Michael in the arms of Moster Anna, Mum, Mormor, Morfar and a pal whose name I don't know.

*

*

Zone S, number 116 in the cemetery at Sundsvall. It says:

KARL GUSTAFSSON

*1868 +1937

HUSTRUN AMANDA

*1872 +1927

DÖTTRARNA

ANNA *1898 +1976 (moster Anna)

GRETA *1901 +1988 (moster Greta)

KLAS GULLIKSSON. (morfar)

*1892 +1968

HUSTRUN SIGRID (mormor)

*1906 +1997

Hustrun = wife

Döttrarna = daughters

Labels: My family history, Myself

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home