Göran Sonnevi: The Ocean

I've just discovered that the celebrated Swedish poet Göran Sonnevi lives in the same town, Järfälla, as my sister. (It's on the edge of Stockholm, at the eastern end of Lake Mälaren.) In honour of that discovery, I'm dipping into Oceanen, Sonnevi's enormous poem of 2005. I thought: let's open the book at random (p. 40 of 419), and begin to translate....

ORMÖGA; SECOND POEM

Here's Ormöga The grey clouds drift over

the level heathland the sea horizon grey

with a glowing streak just above the land

The cuckoo calls The snipe are flying round the fen

The early marsh orchids' dark little torches glow The grass is

greygreenbrown, changing All round are precipices

There's one next to the bed I sleep in Steeply

falling night We float over the darkness, as over

the universe, in its abstraction In the morning we're to-

gether We listen to music I'm listening to nothingness too

In the distance I can see the fishing huts, the chapel ruins

Among them stands the Celtic cross, of lime-

stone, which was itself the crucified with

outstretched arms The hands The head The foot

grown over with grey and yellow lichen Now rain

sweeps across the landscape The hen harrier flew

from the grove towards the sea I shall not have any defence

I'm in the streaming darkness also the pale night

I've set up as a sign

the feather I picked up by the eastern sea

My father and my mother are in the western sea, which I

also touched, with my hands Here are the other dead, the other

living We touch each other's distorted faces

I feel their geometry I see the swallows' flight-curves

here too, quick switches in direction, a constant adjustment

The hen harrier has its geometry, in its flight That's

what we touch, far away, in the distance

The feather is grey within, then brown, then nearly white

Also down at the root there's white, fluffy

The swallows are still building their nest, on the outside the clay is moist

Ay! Ay! That dark face rests behind all this

The landscape here moves in a seemingly

older economy Same dry-stone walls, same fields

as from another time The birds The orchids Yesterday

we went to the sea; within the pine grove grew

a very large specimen of Military Orchid,

Orchis militaris, pale lilac, a big spike, thick stem

Down by the sea I went to the place with Blood Orchid,

flecked leaves, boldly marked flower-lip, beside

the Early Marsh Orchid, a deeper lilac The black-tailed godwit flew up

The cows, young heifers, formed themselves into a line in the distance

Farming going on The smell of liquid manure in the rain, under

the mists On the sea cargo boats go by On the thrift's

stem glowed the lackey moth's larvae in the evening sun, with red-brown

hairs, above the light blue and brown stripes along the body

We are in a network of dependencies Who is it that's murdered?

Who do I murder? Everything depends on the way we touch each other

In Ormöga the blind man lives, alone, since his mother died

a couple of years back When I pick up the post from him

he turns his ear's glance towards me while we talk

In his face is a kind of peace The garden runs ever more wild

We're renting here at one of his sisters', in one of the houses

facing the sea Most of them are leased out now I told her

about Gunnar and Verner in Färgaryd, how they kept a calf

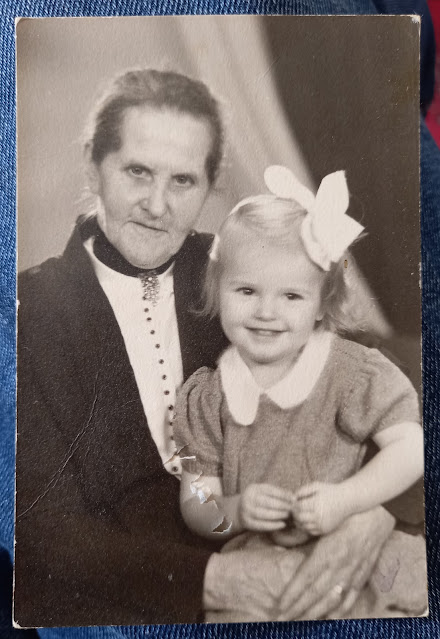

This talk touched my childhood I'm getting ever more childlike now

Today is the last day of the year since my mother's death We'll be lighting a candle

Everyone's asleep Everyone is as if they were awake

in the first moment of dawn The landscape entirely still

My mother has been dead for a year Now I'm wholly alone

My child is asleep You're asleep, dear one Everyone should sleep

In the morning we light the candle in the window in the sun

between us and the sea Here is Ormöga, where we were meant to be

a year ago We are here for the second time

What do I see with the snake's glance out towards the sea In my

self-sufficiency, in my lack of interest for the

life of others The indifferent's geometry My tower here is

turned towards the sea, since the proprietress locked the other room

I shan't break open the other's room Only my own

Yet nothing can be repeated The swallows' geometry is constantly new

Perhaps we go into each other's room As into a chamber of Hades?

We will be in each other's intolerance There love finds us

My mother has gone in to my silence, is now part

of it There she can no longer disturb me It's

not required now either She touches me with every leaf

In the grey afternoon I go alone to the sea

The black-tailed godwits fly up, circle around me, cry

The curlew flies up too In the pine grove by

the sea a red-brown cow has got over the dry-stone wall She

follows me with her gaze I follow her Down by

the sea I touch the water, follow the beach Look for

avocets in the bay towards Kapelludden, but there aren't any

My mother's silence breathes I am in my breath The deep

voice is heard, within me, in the silence Whose turn is it now?

Ay! Ay! The swifts' young are flying, already supreme I breathe

in Genders, animals, creatures, society, people They breathe

also within me I delete nothing The voice is in its

divisions, infinitely subtle It isn't subject to anyone

I'm waiting for the dark pain That will come

and break its way in as my mother She comes also as

a woman, and I rest in her transparency

She's terribly jealous, doesn't tolerate that I'm

with anyone else There is no sleep I'm with my dear one

We are lying within the extended sofa's wooden frame

Over the heath and the wood stands the moon, a bit bigger than a sickle,

waxing It shines with silver-gold light in the pale night

Still June Later in the night I hear the shriek of the black-tailed godwit

July Through the open window comes air from the sea

Listen to the swallows, their small chirping sound Far off

is heard the curlew The grief for my mother comes, outside time, it doesn't

bother about time Saw her smiling hugeness, when she no

longer was sad The vastness without reserve, just in existence

Here's Ormöga The pain has no time The joy neither

The sea glitters in the distance On the shoreline saw the beck's cleft

I still wait for the pain to break into the future, into its

dark forms I see the angel of the annunciation on the font at Egby,

Gotland sandstone, 11th century It flies like the birds of the dead

on the picture-stones some centuries earlier But with a glory round

the head, above the wild animals who attend Mary

In another scene she rests wrapped up, half sitting

on a bed, Joseph gives her something to drink We go to

the little alvar behind Bockberget to the west There we see the cranes stepping

Yellow sedum's blooming, and white, half out A little

tuft of thyme glows lilac On a dark limestone slab a light-coloured stone,

some kind of sandstone, mossy, hollowed out A cranium

You stretch out on the warm slab, rest there In the distance

I see you as some animal, green- and black-flecked, that doesn't exist

At night the swifts flew before the moon, nearly half full A

single star appeared, scarcely distinguishable, in the pale night

The noise of rain on the roof Here too in the tower of nothing

Gösta Skyle We'll be going straight from here to his burial

He's the last of the people from my childhood At his home was

the same luminosity, the same kindness as at my dad's Not his torment

I didn't see that until now, in the contrast, in death

Grasp that my father didn't want to be what he was At Gösta's I saw

a different society stand out Where nothing's sold Nothing bought

See that my father fled from his mum's torment, her hardness, dominance

Helge related how he used to get up in the night with the potty full of blood

She forbad Gunnar from marrying, after he came to grief in America

when the bank that held his savings went under, and he was forced to live

in someone else's house as a farm-hand Farfar wrote to him, when he was called up

in the summer of 1941, about the harvest, and that he hoped he wouldn't have to

go to war Seeing before me Gösta's parents, August and Selma, Gösta

took after her, remember the hornet's nest I stirred up when as a child I said:

Farbror Svensson is a Nazi Who has said that? Where did you hear that?

The adults in a ring round me, disturbed I understood nothing about it

Don't know, but I have no reason to think it was true

He was a grocer in Vattugatan in Halmstad, a little shop

in the basement of the big apartment block, bowed metal roof over the stairs down

His children, Gösta and Helfrid, wanted to be artists; he became a drawing master,

she became a telephonist The other son, Sture, became a chemist; when I was

nine or ten, maybe eleven, I visited him at Chemicum in Lund

All that I see Ay! Ay! Nothing of everything Everything of nothing

The tower of nothingness is emptied The hen harrier stops with

fluttering wings above the beach heath I go out in the sun

look at the rock-roses in the grass, the burnt orchids and the

twayblades Hear the waves, and far off the black-tailed godwit

In the night I heard the nightjar, while visiting friends

We came home over the Alvar beneath the moon Then northward, getting

under dark clouds, in the rain Here all the birds are sleeping

The swifts sleep under the roof tiles, with their long,

slender bodies We sleep beside each other I've drunk wine

Not you, who drove This tower is emptied Others will come

Slenderer, with their roots far down beneath the earth

The water presses up through the limestone pavement Meets the rain there

I heard the nightjar sixteen years ago in the same place We are older

I see a woman's sex, bright, upright, a narrow mandala

I pass in there Into its darkness In a violent emptying

I see history's face Wolves pressed into Paris, through

breaches in the wall Ay! Ay! We shall be here with each other

The sea sees me, with its horizontal glance Level with the eyes

Yesterday I went to the mother-sea, also here There are all creatures now

All those who see each other The fox, the cat Cows there in the distance

At dawn the fly runs like a sweat-drop over the face It

doesn't sleep The swifts are already flashing past Everyone sleeps

Here is Ormöga Here everything is foreign Here we almost

don't exist Here is the dark-grey sea horizon All the flowers

All the birds Yesterday I saw the swallow's young in the nest nearly above

the dining-room window In the beach heath the curlew's young, while the parents

circled above; smaller, slenderer bill, same call, though smaller

I went the last time to the sea, alone Everywhere water, after

the rain The sea was completely still; I heard its voice, still

This is now my mother's sea too Although she never managed to come here

I touched it It is a returning Here everything is foreign

Here is the hen harrier Here is the snipe, keeping watch

In the night I see the moon go down, orange among the clouds Perfect

solitude; perfect silence While everyone sleeps At dawn the fly wakes us

Ay! Ay! The everywhere vacant torment, in its furthermost presence

The cuckoo is heard, distantly The swifts are in their geometry, dynamic

We take our leave of friends, chat in the dusk, after visiting

the headland the first migrating birds are gathering, dunlins, says the newly arrived

ornithologist in the house next door

Tomorrow Gösta Skyle will be buried in Söndrum outside Halmstad We shall be there

(pp. 40-47)

*

[Ormöga is on Öland, which contains Europe's largest alvar (extended limestone pavement) -- Stora Alvaret -- , and also many orchids.

Blood Orchid = "Blodnycklar", a name given to Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp. cruenta, a dark-coloured subspecies of Early Marsh Orchid.

]

Labels: Göran Sonnevi, Specimens of the literature of Sweden